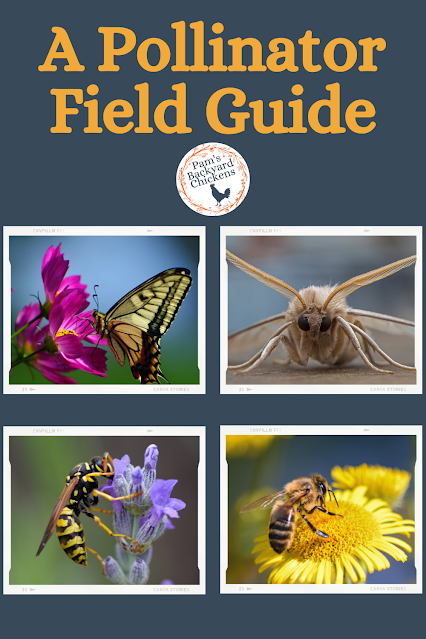

We know that pollinators are important, in fact, they are responsible for one out of every three bites of food we take. This has spurred on a backyard revolution of planting for pollinators. While everyone’s busy making their land animal and insect-friendly, it’s fun to know who’s who in the garden. That way, when you start spotting the pollinators you’ve attracted, you’ll know what you’re spotting and some fun facts about them.

Is an Insect a Bug?

Since insects make up a sizeable portion of the world’s pollinators, chances are those are some of the first pollinators you’ll get a chance to observe. When I worked as a naturalist, I always discussed the words insect and bug because they’re often used interchangeably and thrown around without much thought.

First things first, a bug is an insect, but not all insects are bugs. Bugs are a particular type of insect. This begs the question of what is an insect? An insect can be identified by the following features: an exoskeleton (hard outer covering), three distinct body parts (head, thorax and abdomen), six legs, two antennae and compound eyes.

Pin the image below to save this information for later.

How does the term bug fit into this mix? Bug is a common term for the order of insects known as Hemiptera or true bugs. This order contains some familiar insect species including aphids, bedbugs, water striders, cicadas and stink bugs. What makes them unique? They literally suck — they use their proboscis to suck the juices from plants and even animals. Yes, other insects like butterflies have a proboscis, but the difference is that a butterfly or bee can roll up its proboscis. A true bug cannot retract its proboscis.

Is That a Butterfly or a Moth?

It’s funny because this is a question most don’t give any thought, but it can sometimes be a challenge. Butterflies and moths belong to the order Lepidoptera which translates in Greek to “scale wing” — Lepidos for scales and ptera for wings. Aside from beetles, Lepidoptera is the largest order of insects with over 120,000 species worldwide around 14,000 of which reside in North America alone. Numbers vary on this from source to source. These are from my trusty Golden Guide to Butterflies and Moths. Sufficed to say, there are a lot of butterflies and moths in the world around us. So if you’ve ever been the recipient of this seemingly simple question (especially from your kids) then it’s good to know some clues to help you identify your winged visitors.

Time of Day — The general rule of thumb is that butterflies are active during the day and moths are active during the night. There are, however, exceptions to the rule. One of the coolest exceptions is the hummingbird moth. At first glance, you may mistake this day-flying moth for its namesake, but look closer. A member of the sphinx moth family, this moth hovers in front of flowers sucking nectar just like a hummingbird.

Coloration — Butterflies are generally bright and colorful so they blend in with the flowers they visit. Moths get the short end of the stick here; most are dull colored. Since they fly at night, they don’t have much need for colors. Although I have to say, their browns, blacks and grays often have wonderful patterns that do bear admiration.

Resting Stance — Notice how your winged insect sits when it stops flying. Butterflies rest with their wings held up together. When moths rest, their wings lie flat; held close to their sides, covering their back.

Antennae — If you can get a close up look, you should take a peek at your insect’s antennae. The antennae of butterflies are usually clubbed at the end. A moth’s antennae are normally feathery.

Body Shape — Moths usually have a thicker, more hairy body while butterfly bodies are much more streamlined.

Life Cycle — No matter whether you’ve found a moth or a butterfly, both start life from an egg that hatches into a caterpillar which then forms into a pupa that transforms into an adult. The difference is in the case that encloses the pupa. Butterflies form a hard case called a chrysalis that in some cases is notable for its beauty. For example, Monarch butterflies form a mint green chrysalis with gold accents. Moths form a cocoon case from silk threads that looks hairy and a little untidy. Skipper butterflies are an exception to this rule. They form a cocoon around their chrysalis.

In the end, only a butterfly/moth nature guide will help you correctly identify the exact species you’ve spotted. But, these quick tips will help you narrow down your search and satisfy your curiosity; is it a butterfly or a moth?

Is That a Bee or a Wasp?

While viewing butterflies on your pollinating plants is fun, it’s a practice that should be done with care since you don’t want to scare away your quarry and you don’t want to get stung. Don’t get me wrong, butterflies don’t sting, but bees and wasps can! If your pollinator garden is anything like mine, you’ll have a few butterflies at a time flitting around your flowers accompanied by lots of bees buzzing around. My flowering basil plants are a particular favorite for bees, sometimes you can walk by and hear the buzzing coming from each plant. It can be tricky not getting stung if you want to get some great pollinator pictures for articles like this one!

Don’t let a sting deter you, let your curiosity entice you to take a closer, if not more careful, look at what’s buzzing around. On closer inspection, you may be astonished that not all those insects you’re spotting are bees, in fact, some are wasps and even flies. They are called bee mimics. Here’s how to tell the difference.

Tip: Bees and wasps will usually not sting unless they feel threatened, however, there are some wasps that are more aggressive than others. Social bees are also more likely to sting than their solitary-living counterparts because they are defending their colony. A single bee will sting only once, but a wasp can sting multiple times.

Bees and wasps belong to the insect order Hymenoptera. Flies belong to the order Diptera. Bees, including honeybees, and wasps both create naturally occurring nests, but bees produce honey, wasps do not. Some wasps are easily distinguishable by the telltale paper nests you can find hanging in trees or inconvenient spots like above the front door or under the deck steps. Bees don’t make these paper nests. You’ll notice, I’m not using the word hive for bees, a hive is a man-made structure for honeybees only.

Speaking of pollen, bees eat pollen and nectar from plants. They use that pollen as a source of protein for their young. Wasps use meat as the source of protein for their young. Both flies and wasps eat other insects, but not bees, they’re natural vegetarians.

Wasps and bees both have four wings while a fly only has two. Wasps and bees have chewing mouthparts while flies have sucking mouthparts. Both bees and wasps have long antennae while flies have short kind of feathery antennae. Some flies actually can be identified as such because their eyes are located together at the top of their head while bees and wasps have eyes toward the side of their head.

Bees have a more substantial, thick and rounded body than a wasp. A wasp’s body is slender, smooth and has a skinny waist. Wasps will also have smooth legs whereas bees have hairy legs for gathering pollen.

Raising Butterflies and Moths

The lifecycle of butterflies and moths fascinates many, including me. It’s fun to raise butterflies and moths to give nature a helping hand and to see the process unfold; especially if you have kids.

Butterflies and moths undergo a complete metamorphosis which includes four life stages — egg to caterpillar (larvae) to chrysalis (pupa) to adult.

You can raise your insects from any of the first stages, but frankly, butterfly and moth eggs are really small, hard to find and cannot be removed from the leaf where they are attached. If you want to raise the egg, remove the whole leaf. Most people find caterpillars in the garden and go from there. There are mail-order companies that sell butterfly kits. Those usually come with the live caterpillars to raise.

Before you start, it’s a good idea to invest in a field guide that helps with identification not only of the adult butterflies and moths but also what they look like in their caterpillar form.

When you find a caterpillar, take note of where it is and what it’s eating. (This is the same for an egg.) This is crucial because each caterpillar has a specific host plant or plants that it can eat. You cannot substitute other plants. The caterpillar will not live. The most famous example of this is the Monarch butterfly. Its caterpillars can only eat milkweed. Be prepared to provide your caterpillars with fresh leaves every day. Caterpillars eat a lot!

Caterpillars should be kept in a protected container outside. We have a screened-in porch where my kids keep their caterpillars out of direct sun and weather. We use a wonderful mesh cage with a removable bottom that was once an anole/reptile cage. The removable bottom is perfect for cleaning caterpillar poop. They make a lot of it! You can buy specific butterfly/moth homes. You can also repurpose an old aquarium and use a mesh lid to allow ventilation. The caterpillars will need some branches so they can climb. The butterflies may use the branches to hang as a chrysalis and both will use the branches when they emerge to hang upside down and dry their wings.

You’ll notice the chrysalis changes as the butterfly moves closer to emerging. This is really obvious with Monarch butterflies. The chrysalis changes from mint green to a clear shell where you can see the dark butterfly inside.

When you have a butterfly or moth emerge, do not jostle or touch it, their wings will need to dry. Once dried, you can release your butterfly in your pollinator garden during the day and your moth in the pollinator garden during the evening.

Have fun!

This pollinator field guide was originally published in The New Pioneer magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment